Good Letters: What Beast To Be Born?

In times of strife, we turn to poetry. But prose has its place, too.

Because, well, 2020, I’ve found myself reaching for poetry lately.

I’m not a poetry buff (I wish I were). Despite being an English major, and the daughter of a poetry enthusiast who can rattle off verses at will, I find poetry incredibly difficult. If you read it out loud to me, I have some sort of mental block that stops the words from landing into meaning. And so, with each poem I come across, I must read it, multiple times, underline or circle, look up a word or two, until I feel like I can grasp it. But, I think because I have to work so hard to unlock them, I get so much more out of them than prose. They make me feel and think deeply. And, at a time like now, when we’re all at sea, each poem feels like a little guiding life boat of introspection.

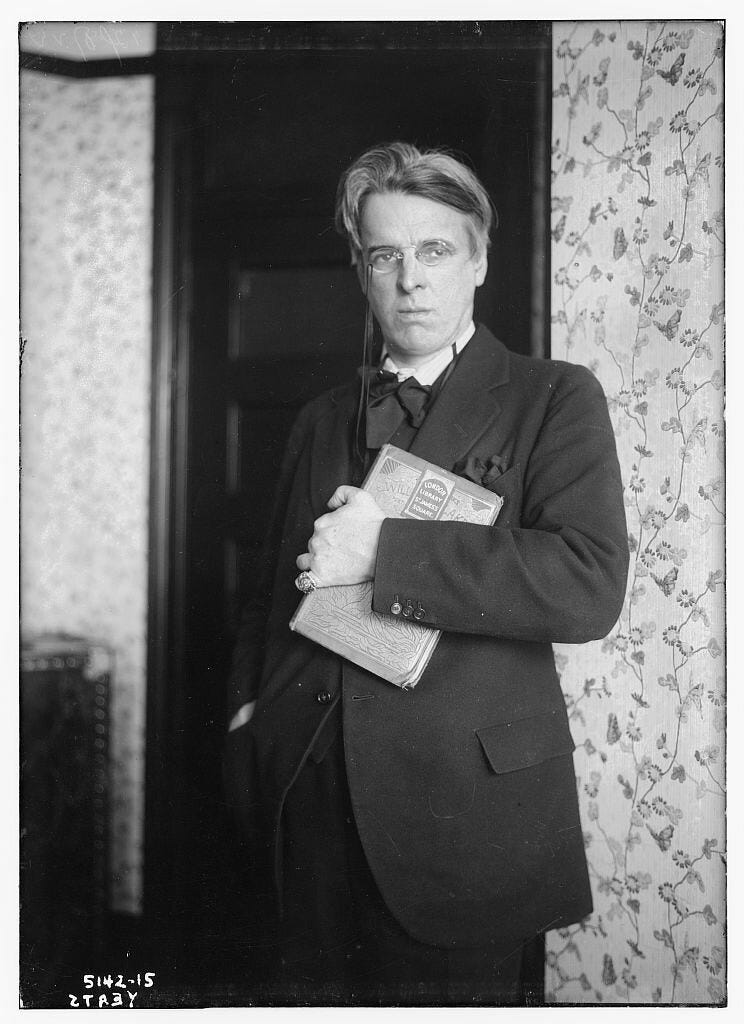

In college I took a course on Irish Literature that gave me the opportunity to grapple with the works of the great Irish poets. And, of all of them, W.B. Yeats stuck with me most. As did his — arguably — greatest work: “The Second Coming.”

When I went back to it recently it was, indeed, as powerful as I remembered. And, when I briefly researched its origins — Yeats wrote it while his wife recovered from the deadly flu of 1918, in the aftermath of World War I, and in the beginnings of the Irish War of Independence — I realized why it felt more resonant to me than ever.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

"The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity." That sounds like 2020 all right. And I, like a lot of us I'd wager, am anxious that the rough beast has already been born, that perhaps at this moment it's running the streets of New York City, and the end is nigh.

BUT — I don’t want to end this blogpost there. After all, if there is one thing we believe here at Uncertain, it’s that we mustn’t let ourselves wallow. And while poetry is excellent for deep reflection and inner awakening, I find prose better suited to inspiring forward motion.

And so, to re-invigorate myself (and you dear reader) with some cautious optimism for our collective future, I’d like to share a work of prose from a storyteller I admire: Oliver Sacks. Sacks died in 2015, and I'm not sure when exactly he wrote this, but I think it's more true now than then. Here's a short excerpt of the ending, but I encourage you to read the essay (which isn't long) in full.

As one’s death draws near, one may take comfort in the feeling that life will go on—if not for oneself then for one’s children, or for what one has created. Here, at least, one can invest hope, though there may be no hope for oneself physically and (for those of us who are not believers) no sense of any “spiritual” survival after bodily death.

But it may not be enough to create, to contribute, to have influenced others if one feels, as I do now, that the very culture in which one was nourished, and to which one has given one’s best in return, is itself threatened. Though I am supported and stimulated by my friends, by readers around the world, by memories of my life, and by the joy that writing gives me, I have, as many of us must have, deep fears about the well-being and even survival of our world.

Such fears have been expressed at the highest intellectual and moral levels. Martin Rees, the Astronomer Royal and a former president of the Royal Society, is not a man given to apocalyptic thinking, but in 2003 he published a book called “Our Final Hour,” subtitled “A Scientist’s Warning: How Terror, Error, and Environmental Disaster Threaten Humankind’s Future in This Century—on Earth and Beyond.” More recently, Pope Francis published his remarkable encyclical “Laudato Si’, ” a deep consideration not only of human-induced climate change and widespread ecological disaster but of the desperate state of the poor and the growing threats of consumerism and misuse of technology. Traditional wars have now been joined by extremism, terrorism, genocide, and, in some cases, the deliberate destruction of our human heritage, of history and culture itself.

These threats, of course, concern me, but at a distance—I worry more about the subtle, pervasive draining out of meaning, of intimate contact, from our society and our culture. When I was eighteen, I read Hume for the first time, and I was horrified by the vision he expressed in his eighteenth-century work “A Treatise of Human Nature,” in which he wrote that mankind is “nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement.” As a neurologist, I have seen many patients rendered amnesic by destruction of the memory systems in their brains, and I cannot help feeling that these people, having lost any sense of a past or a future and being caught in a flutter of ephemeral, ever-changing sensations, have in some way been reduced from human beings to Humean ones.

I have only to venture into the streets of my own neighborhood, the West Village, to see such Humean casualties by the thousand: younger people, for the most part, who have grown up in our social-media era, have no personal memory of how things were before, and no immunity to the seductions of digital life. What we are seeing—and bringing on ourselves—resembles a neurological catastrophe on a gigantic scale.

Nonetheless, I dare to hope that, despite everything, human life and its richness of cultures will survive, even on a ravaged earth. While some see art as a bulwark of our collective memory, I see science, with its depth of thought, its palpable achievements and potentials, as equally important; and science, good science, is flourishing as never before, though it moves cautiously and slowly, its insights checked by continual self-testing and experimentation. I revere good writing and art and music, but it seems to me that only science, aided by human decency, common sense, farsightedness, and concern for the unfortunate and the poor, offers the world any hope in its present morass. This idea is explicit in Pope Francis’s encyclical and may be practiced not only with vast, centralized technologies but by workers, artisans, and farmers in the villages of the world. Between us, we can surely pull the world through its present crises and lead the way to a happier time ahead. As I face my own impending departure from the world, I have to believe in this—that mankind and our planet will survive, that life will continue, and that this will not be our final hour.

— v